For weeks now I have been dealing with things: unpacking and repacking them, dusting them off, sorting them out, holding them in my hands, throwing them away.

About two weeks ago, my mom and my aunt and I went to out to my grandparents’ house in Missouri to pack it up, to begin to get it ready to sell. We moved them up to Minnesota almost ten months ago, and since then the house has sat still, their aging black lab wandering aimlessly and heavily in and out of his dog door to garage, being fed by a family friend, the swimming pool hosting gleeful clans of mosquitoes. Various children have come by a few times: the fridge was cleaned out, the books were sorted, choice pieces of furniture were taken. Most of the beds got clean sheets. But that has been it.

When we got into town we went by Walmart to get cleaning supplies: paper towels, trash bags, work gloves, lighter fluid, and matches. Over the course of five days we sorted through about half the house. My grandparents lived in that house for more than fifty years, and for people who I know have stored up their treasure in heaven, they have so, so much stuff.

Highlights included a book of Ronald Reagan “full color” paper dolls, three Chinese checker boards, a forty-year-old speed reading course neatly packed in its own blue case, hundreds and hundreds of cassette tapes, three doctor’s bags full of hypodermic needles and prescription medication dating back to the seventies, drawers and chests full of baby and doll clothes, a 1993 picture of grandkids at a family funeral which someone had had produced as a jigsaw puzzle and then never opened, a ziplock bag of stockings neatly labelled as “Not Best Stockings”, designer ties mixed in with the polyester ones, boxes and boxes of microwave popcorn, dozens and dozens of Mason jars (some still containing homemade jelly,) and boxes of old forgotten family correspondence, all along with seven dead mice, thousands of mouse droppings in drawers and corners and plastic bags, and one small wasps nest.

We sorted things into piles to sell, to give away to the local charity shop, to take home with us, to go in the dumpster, and yes, largest of all, to throw on the fire out back. I carried huge bags out to toss onto the flames, and sometimes I would stand and watch them burn: all of these things which had sat so patiently at the back of a crawl space or at the back of a drawer, now gone so fast. Pages and pages of old medical journals turning ashy black, their edges curling and disintegrating. Boxes of ant-infested sugar cubes turning into syrupy brown rivulets, burbling down the side of the heap.

On our drive out to Missouri my mom told me about the paper she was writing for the conference she and my dad are at this week, and she explained that in ancient times, when education placed a great emphasis on memory, particularly memorized oratory, teachers taught their pupils to use a device called the “house of memory.” As a young man memorized his speech he was supposed to build a big house in his mind and walk through it as he recited. Each room was supposed to remind him of a different point or counterpoint, and then lead smoothly onto the next point in the next room. If you stayed safe within your illusory house as you spoke, you would not get lost in your own words.

I am very good at remembering: my sister and I have a running joke that I remember her own life better than she does. And because I am good at memory, I prize it very highly: to remember what has happened feels like having all the answers stored away for a rainy day.

And my grandparents’ home has always served as a tangible house of memory for me: It is the center of my extended family, the place I can remember all of them and all of our Christmases and summers. As we packed up the end room, and piled old appliances and furniture in the middle for the dumpster, I kept looking around and thinking about my uncles who grew up here when this was “the boys’ room”: they have gotten tall and grey, but the wooden paneling and the bright blue carpet still remembers them as scruffy loud little boys, reading Peanuts books, just as the now busted out doctors bags remember all the patients my grandpa cared for so faithfully, and the Mason jars remember my Grandma’s hard, satisfying work over a hot stove.

I know that memories can be a burden. But I also know that my grandparents are so old and have forgotten so much. If I cannot remember things for them, I wish I could at least hold onto the things that saw them when they did remember. But I know that it is better to try to live with empty hands.

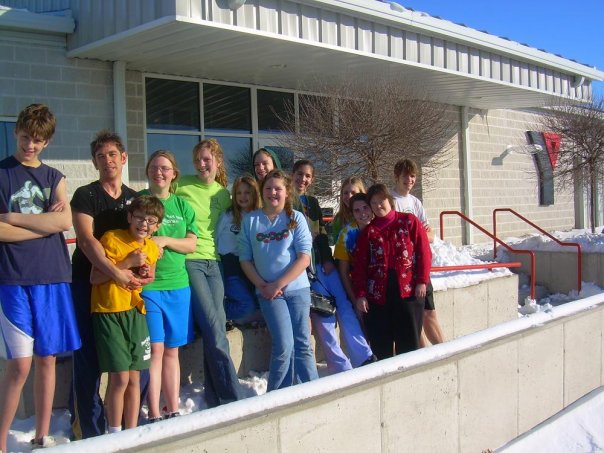

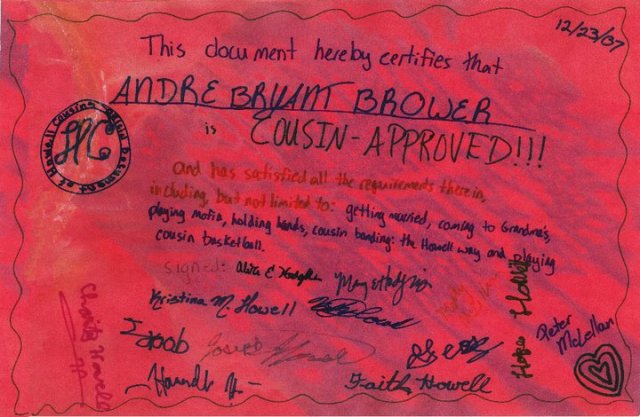

Tomorrow I am moving into my first real apartment, so I have spent the last several days packing. While I do not hoard, there are certain things I have quite a lot of: I have a lot of dresses, tights and blankets, I have twelve boxes of books, and I have huge amounts of paper: mostly in ratty old notebooks of different shapes and sizes. Most of these things (except some of the paper) will come to my new home. I will not stay there forever: the new memories I will make in the rooms will become old, and I will leave them behind. It’s unavoidable, I’m going to forget. I’m going to forget my sixth grade email address and why I chose it. I’m going to forget what my cousins looked like when they were babies, I’m going to forget what year I took that favorite class in college, I’m going to forget students’ names, I’m going to forget what I did on my nineteenth birthday.

And someday I will probably forget that my grandma read Proverbs at the breakfast table. But she did not read Proverbs to her children and grandchildren so that we would remember that she read Proverbs at the breakfast table. She read Proverbs so that they would they would teach us to strive to “get wisdom” and “keep understanding.” And they did. They do. She would not mind if I forgot all the rest, so long as I remember that.

The old that is strong does not wither / Deep roots are not reached by the frost.